On August 14, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act into law. The program was designed to give private sector retired workers old-age benefits. In the ninety years since, the program has grown in both size and scope. It is currently the single largest expenditure in the federal budget, and nine out of 10 Americans age 65 and older are receiving a Social Security benefit.

But a just-released survey of 2,200 Americans from the Cato Institute shows that most know very little about how the Social Security program works. Many do not understand, for example, its pay-as-you-go funding approach. They incorrectly presume that the program has accumulated assets on their personal behalf like a traditional pension.

In an effort to remedy this and other misconceptions, this article will examine the program’s history and how the evolution of Social Security led to the challenges it currently faces.

The Push for a Social Safety Net

We can infer from both words and deeds that FDR’s primary goal in creating the Social Security program was to provide social insurance, a phrase he used many times that had already come into widespread use since being introduced by Otto von Bismarck in 1889. FDR also made it clear that his goal was not to produce a utopian outcome, but to ensure that no one would have to suffer terribly from “…the vicissitudes of life.”

From the very beginning, however, the goal of having the government provide insurance against bad outcomes was conflated with the goal of increasing equality. This tension is evident from debates among the program architects of Social Security, as documented in economist Sylvester Shieber’s 2012 book The Predictable Surprise. This debate was never settled. Bargaining among the program’s architects simply continued until the program achieved a mutually acceptable balance between these two goals.

From 1937 until 1940, Social Security paid benefits in the form of a single, lump-sum payment for those who paid into the program but did not participate long enough to be vested for monthly benefits, with monthly benefits beginning in 1942. The earliest reported applicant for one of these lump-sum benefits was Ernest Ackerman, who retired one day after Social Security began in 1937. During his one day of participation, a nickel ($1.12 in current dollars) was withheld from his paycheck for Social Security. Upon retirement the next day, Ackerman received a lump sum payment of 17 cents ($3.81 in current dollars), more than triple the value of what he paid into the program!

The first recorded recipient of monthly benefits was Ida May Fuller. She paid into the program for three years, a total of $24.75 ($570.24 in current dollars) by 1939. Her first monthly check, issued January 31, 1940, was worth $22.54 ($519.32 in current dollars), collecting a total of $22,888.92 in benefits by the time of her death in 1975, a 925 percent return on what she paid into the program.

Social Security’s Growth in Size and Scope

FDR insisted that the program be a fully self-funded pension program. Although he understood that initially self-funding was impossible, he strongly opposed the use of extracurricular federal funding as an ongoing practice. His primary goal was not redistribution but to use government to provide a social insurance mechanism to ensure that no American would be impoverished in old age. Except for short-term budget smoothing, once the program was in balance it should stay that way.

By 1939, Social Security was extended to spouses of retired workers, children, and survivors of deceased workers.

Contrary to FDR’s wishes, not long after his death, the program expanded its scope and its size and emphasis on income redistribution. The program did, however, continue to rely on pay-as-you-go budgeting.

In 1956, Disability Insurance was added, covering workers aged 50-64 who became permanently disabled as well as disabled adult children of retired, disabled, or deceased workers. Then, in 1960, disability coverage was expanded to disabled workers of any age if they met work and disability criteria. Soon thereafter, the old-age insurance was expanded to include farm workers, domestic workers, self-employed, as well as state and local government employees.

In 1972, the federal government passed P.L. 92-336, which authorized a 20 percent cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) effective in September of that year and established the procedure for issuing automatic COLAs each year beginning in 1975. Finally, federal employees hired after 1983 were eligible to receive reduced Social Security benefits in addition to their federal pension. This changed in 2024, when the Social Security Fairness Act was passed, allowing federal employees to receive full old-age insurance benefits along with their federal pension.

As promises proved to be more generous than what payroll taxes could cover, the threat of insolvency continued to grow.

The Current Crisis

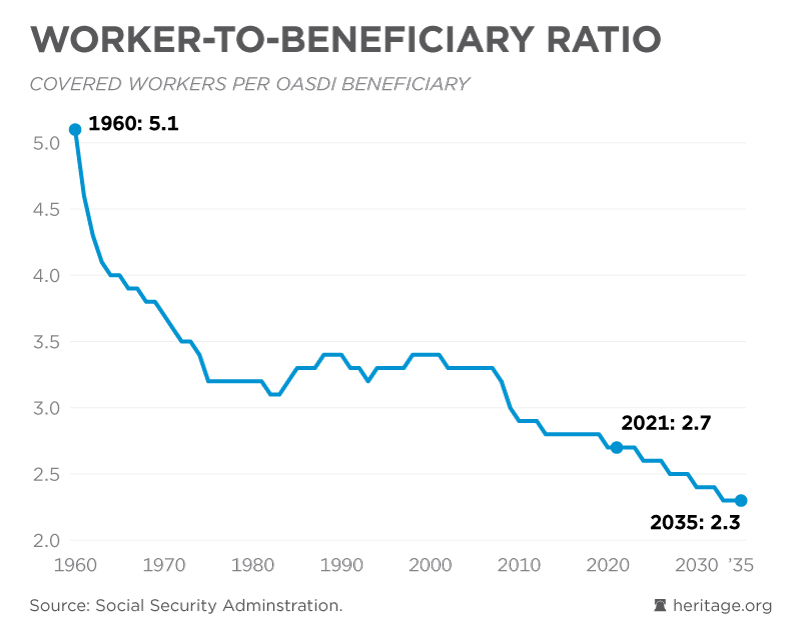

Although Social Security was meant to be a self-funding program, to quickly begin providing benefits to the elderly poor pay-as-you-go budgeting was required. Given the high ratio of workers to citizens over the age of 65 at the time, this was politically palatable because only a small payroll tax was required to fund the program.

But this opened the door to insolvency from increasingly generous promises that could not be covered out of payroll tax revenues when demographics became less favorable (by 2021 the ratio of workers to recipients and fallen to 2.8). Even after 20 payroll tax increases from 1950 to 1990, the irresponsible expansion of benefits left the program with a persistent operating deficit that now threatens the ability to deliver genuine social insurance.

Even in years when the so-called trust fund was being drawn down to cover the operating deficit, additional borrowing by the Treasury was required because the funds in the Social Security trust fund were illusory (The Entitlement Collapse Is Worse Than It Looks).

The slew of recent revisions to when the Social Security trust fund would run out in the aftermath of the Social Security Fairness Act and the enactment of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) are therefore a distraction. We are already increasing the federal debt each day to cover the redemption of assets in the Social Security and Medicare Part A trust funds, so when the funds run out that process can simply continue as before – until it can’t.

The real problem is the remaining unfunded obligation problem, which has also jumped in response to these two most recent events. Over the next 75 years, its unfunded obligation problem has jumped up to $28 trillion.

Moody’s recent downgrading of the US government’s long-term debt instruments is but one piece of growing evidence that we are entering a debt cost spiral due to the increasing debt burden feeding on itself as rising interest rates increase the cost of servicing the debt, requiring more debt, and so on. If one thing is clear, Social Security in its current form is not sustainable. Fortunately, there are numerous solutions available to stop a catastrophic meltdown of the program (and the US government at large). The challenge of implementing solutions is overcoming those both in government and the private sector who have strong incentives to maintain the status quo.