It comes as no surprise that divorce is harmful for children. Most would likely highlight the emotional strain imposed on children from the loss of normal relations between parents, but harmful effects can be economic. Dividing the family into two households means lower incomes and financially costly negotiations, which could impact children over the long term.

Some argue that bad relations between still-married parents would have the same (or worse) negative impact. By this reasoning, the negative outcomes of divorce are based on the underlying issues that cause the divorce rather than the divorce itself.

A new paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) by economists Andrew C. Johnston, Maggie R. Jones & Nolan G. Pope helps adjudicate the question of whether divorce itself is harmful, or if the detrimental effects are merely the result of unhappy parents.

Let’s look at their results.

The Immediate Damage of Divorce

To account for the damage of divorce, the authors highlight several negative changes caused by divorce. First, divorce increases the distance between parents, with the average distance being 100 miles. This limits children’s access to their parents.

Second, household income falls with the division of the household. This decline in income isn’t made up for by child support. The authors state, “combined, these increases [child support and welfare] in non-taxable income offset less than 10 percent of the drop in average household income.”

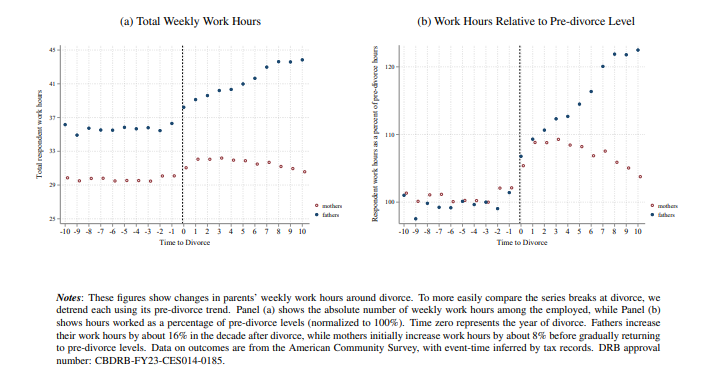

As a result of being unable to pool familial resources, parents work more and therefore see children less. They “find that mothers work 8 percent more hours after divorce, and fathers work 16 percent more after divorce.”

Finally, children tend to be relocated, which can be destabilizing, and is made worse by the fact that “divorcing families also move to lower-quality neighborhoods.”

The authors also examine the results of these changes, and they find two additional negative impacts of divorce: increased teen birth rates and increased mortality. These results indicate the immediate economic downside of divorce and how that can negatively impact children, but how do things shake out in the long term?

Long-Term Impacts

Where this new study shines is in examining the long-term impacts of divorce. In order to do this, the authors essentially compare the outcomes of children who are from the same families, but who have different amounts of time being exposed to the divorce.

If two parents got divorced, for example, when their oldest was 15 and their youngest was 5, the oldest would only experience the post-divorce life as a child for 3 years, whereas the youngest would face it for 13 years.

The results are clear. When parents get divorced when children are younger, those children grow up to have lower incomes, on average. By age 25, someone whose parents got divorced before age six will have approximately $2,500 less annual income (or a nine to 13 percent reduction). The older a child is when the divorce occurs, the less negative the effect becomes. In other words, divorce at early ages means worse long-term outcomes.

Similarly, early childhood divorce increases mortality, and the effect diminishes with age. The same trend holds for increases in teen birth. The results about teen birth and incarceration are particularly alarming:

Experiencing a divorce at an early age increases children’s risk of teen birth by roughly 60 percent, while also elevating risks of incarceration and mortality by approximately 40 and 45 percent, respectively.

In analyzing what about the divorce in particular causes these outcomes, the authors find resource reductions drive a large part of the change in earnings, and the change in neighborhood quality drives the increased incarceration effect.

In other divorce impact studies, critics have a wide lane for critique. When statistics show children of divorce do worse, critics could always argue that there is a selection issue going on. For example, you could say, “It isn’t that divorce has negative impacts, it’s that the people who are more likely to get divorced are going to have other traits or behaviors which impact their children’s outcomes regardless.”

Johnston, Jones, and Pope, however, sidestep this critique by comparing children within the same families. If the thing causing the negative impact wasn’t the divorce itself, the divorce shouldn’t make children in the same family have worse outcomes. But it does. This implies that the divorce itself really is a cause of many of the issues, rather than some hidden underlying factor, as critics like to suggest.

These results shouldn’t be surprising. Parenting is a long-term, team project. Early in childhood, parents make plans and establish routines. These plans and routines lay the foundation for the rest of the child’s life. Like any joint project, whether in family, business, or politics, plans are made because the planning process adds value. Scrapping plans is akin to removing an essential part of the foundation.

When divorce occurs, this foundation crumbles at least in part, if not entirely. Laying a new foundation may not be impossible, but it does tend to be expensive, and this research suggests that children bear much of the cost.